SEARCH

How Apple Pay and Google Wallet are used for card theft

SHARE IT

Cybercriminals are constantly devising new ways to steal money from payment cards, using data intercepted online or over the phone. Sometimes all you have to do is touch your card to your mobile phone to suddenly find yourself without money.

Although payment card security is constantly improving, fraudsters continue to find new ways to steal money. In the past, cybercriminals, after tricking the victim into giving them their card details through a fake online store or some other scam, would then create a physical copy of the card by "writing" the stolen data onto a magnetic strip. They could then make purchases in shops and even withdraw money from ATMs without a problem. Although the creation of chip cards and one-time payment (OTP) codes made life much more difficult for fraudsters, they managed to adapt. The shift to mobile payments has made some types of fraud more resilient, but it has also created new opportunities for fraudsters who, after stealing a card number, now try to link it to their own Apple Pay or Google Wallet account. Once they've done this, they then use the account from their smartphone to make payments with the victim's card - in regular stores or even at fake outlets that support NFC.

How card details are intercepted

Such cyber-attacks require large-scale preparation. The perpetrators create networks of fake websites designed to intercept payment details. These websites can mimic delivery services, large online stores, and even bill payment or traffic fine payment platforms. Cybercriminals also buy dozens of smartphones, set up Apple or Google accounts on them and install contactless payment apps.

The "kicker" comes next: when the victim is directed to a fake website, they are asked to link their card or make a mandatory small payment. This requires entering the card details and confirming the card's ownership via an OTP. In reality, however, the card is not actually charged at that moment.

What exactly happens? The victim's data is almost immediately transferred to the cybercriminals, who try to link the card to the mobile wallet on their smartphone. An OTP code is required to authorize this process. To speed it up and simplify it, the criminals use special software that extracts the data and creates a perfect virtual copy of the card. All they then need to do is take a photo of this image from Apple Pay or Google Wallet. The exact process of linking a card to a digital wallet depends on the country and the bank, but usually no other data is required other than the card number, expiry date, cardholder name, CVV/CVC and OTP. All of this can be intercepted in a single attempt and used instantly.

To make their attacks even more effective, cybercriminals use other tricks as well. For starters, even if the victim realizes the danger before hitting the Submit button, any data already entered on the forms is transferred to the criminals - even if it's just a few characters or an incomplete entry. Second, the fake website may report that the payment failed and ask the victim to try a different card. In this way, criminals can intercept the details of two or three cards in a single attempt.

The cards are not charged immediately, and many people, seeing that there is nothing suspicious on their bank statement, forget about the incident.

How money is removed from cards

Cybercriminals can connect dozens of cards to a smartphone without directly attempting to spend money from them. This smartphone, which is filled with card numbers, is then sold on the dark web. It can often be weeks or even months between the data being intercepted and actually being used. But when the unfortunate day arrives, criminals may decide to spend money on luxury items in a physical store by simply making a contactless payment from a phone with stolen card data. Alternatively, they may set up their own fake store on a legitimate e-commerce platform and make charges for non-existent products. Some countries even allow cash withdrawals from ATMs using an NFC-enabled smartphone. In all of the above cases, no PIN or OTP transaction confirmation is required, so the money can be withdrawn until the victim blocks their card.

To speed up the transfer of digital wallets to hidden shoppers, as well as reduce the risk to those making payments in stores, attackers have begun using an NFC relay technique called Ghost Tap. Specifically, they first install a legitimate app like NFCGate on two smartphones - one with the mobile wallet and stolen cards, while the other is used directly for payments. This app transmits, in real time over the internet, the wallet's NFC data from the first phone to the second phone's NFC receiver, which the criminals' partner (known as a "mule") places at the point of payment.

Most payment points in offline shops and many ATMs cannot distinguish the transmitted signal from the original, allowing the "partner" to easily make payments for goods (or gift cards, which make it easier to legalise the stolen money). In the event the "partner" is caught in the store, there is nothing incriminating on the smartphone, just the legitimate NFCGate app. There are no stolen card numbers, as these are stored on the smartphone of the "mastermind" of the operation, who can be anywhere, even in another country. This method allows fraudsters to quickly and safely cash out large amounts of money, because it is possible for several "partners" to pay almost simultaneously with the same stolen card.

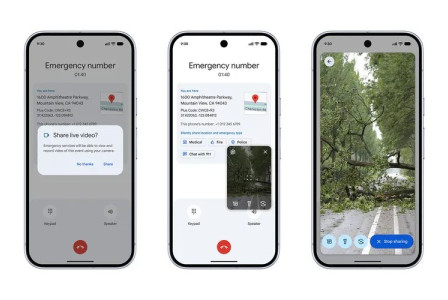

How you can lose money by touching your card to your phone

In late 2024, fraudsters built a new variant of NFC relay and successfully tested it on users from Russia, and there is nothing to stop this campaign from expanding globally. In this case, the victims are not even asked to provide their card details. Instead, using social engineering tactics, the attackers convince them to install a supposedly useful application on their smartphone, pretending it is a government, banking or other service application. Since many such banking and government apps in Russia have been removed from official stores due to sanctions, unsuspecting users easily consent to their installation. The victim is then asked to insert their card into the smartphone and enter their PIN for "authorization" or "verification" purposes.

As is obvious, the installed application has nothing to do with its description. In the first wave of these attacks, victims received the NFC relay, which was presented to them as a "useful application". The app read the card when they inserted it into the smartphone and transmitted its data along with the PIN to the attackers, who used it to make purchases or withdraw cash from NFC-enabled ATMs. The anti-fraud systems of major Russian banks quickly learned to detect such payments due to differences in the geographical location of the victim and the payer, so in 2025 this method changed, but not its essence.

The victim now receives an application to create a copy of the card, while the NFC relay is installed on the attackers' side. Then, citing the risk of theft, the attackers convince the victim to deposit money into a "secure account" via an ATM, using their smartphone to authorise the payment. When the victim touches their phone to the ATM, the scammer transfers their own card details to it, and the money ends up in their account. Such actions are difficult to detect by automated anti-fraud systems, as the transaction appears perfectly legitimate - that is, that someone simply went to an ATM and deposited money on a card. The anti-fraud system does not know that the card belongs to someone else.

How to protect your cards from fraudsters

First, Google and Apple, together with the payment systems, will have to implement additional protective measures in the payment infrastructure. However, users can also take measures to protect their cards:

- Use virtual cards for online payments. Do not keep large amounts of money on them and only renew them before making an online purchase. If the card issuer allows it, disable offline payments and cash withdrawals from these cards.

- At least once a year, replace your virtual card with a new one and block the old one.

- For offline payments, link a different card to Apple Pay, Google Wallet or similar services. Never use that card online and if possible, use the mobile wallet on your smartphone when paying in stores.

- Be very wary of apps that ask you to have your payment card on your smartphone, let alone enter your PIN. If it's a well-known and trusted banking app, then no problem, but if it's something suspicious that you just installed from a link outside the official app store, avoid it.

- Use plastic cards at ATMs, not NFC-enabled smartphones.

- Install a comprehensive security solution on all computers and smartphones to reduce the risk of getting caught on phishing websites or installing malicious apps.

- Enable the Safe Money feature, available on all our security solutions, to protect your financial transactions and online purchases.

- Enable the most immediate transaction alerts (via message or push) for all your payment cards and contact your bank or card issuer immediately if you notice anything suspicious.

MORE NEWS FOR YOU

Help & Support

Help & Support